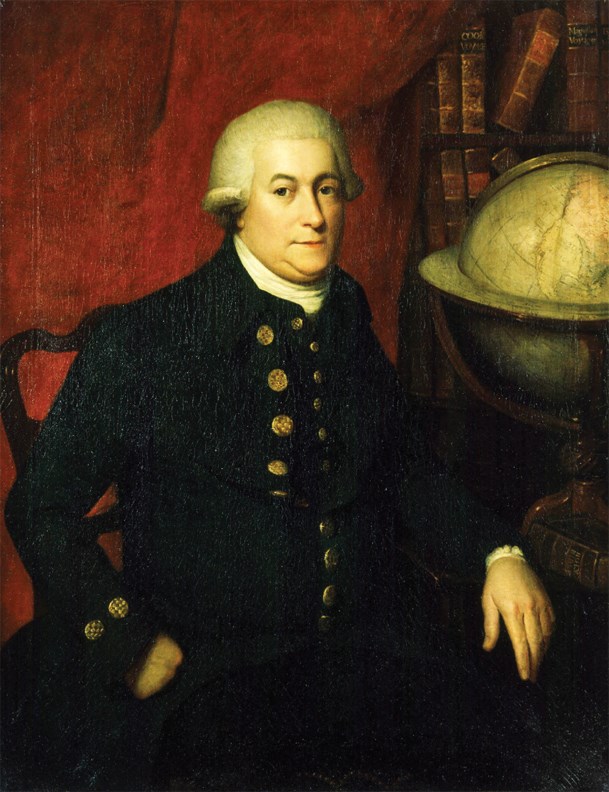

This year marks the 225th anniversary of the arrival of Capt. George Vancouver on the Sunshine Coast. He was born in King’s Lynn, England in 1757 and is best known for his exploration and meticulous survey of the northwest coast of North America from northern California all the way to Cook Inlet, Alaska in 1792, 1793, and 1794. He established once and for all that there is no northwest passage between latitudes 39° N and 61° N, much to the chagrin of King George III who coveted control of a quicker trade route to the Pacific from Europe. It would not be until 1869, with the opening of the Suez Canal, that eastbound ships could avoid going all the way around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope to reach the Far East. Westbound ships would have to wait until the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 to avoid navigating the perilous Straits of Magellan or Drake Passage at the southern tip of South America.

In June of 1792, when Vancouver was just 34 years old, his flagship Discovery and armed tender Chatham emerged from Juan de Fuca Strait and anchored in Birch Bay, just south of the 49th parallel. It had taken the 145-man expedition over 14 months to get there from England. It was from this anchorage that Vancouver and a crew of 30 left on a memorable 11-day survey of the southwest coast of British Columbia using two small longboats under power of oar and sail. The second longboat was commanded by Lt. Peter Puget, who two weeks earlier had surveyed what is now known as Puget Sound in the Seattle area of Washington State.

During this survey, Vancouver explored Burrard Inlet, Howe Sound, the length of the Sunshine Coast up to Pender Harbour, and Jervis Inlet to the end of Queens Reach. He travelled over 500 km in the process.

Vancouver first entered the waters off the Sunshine Coast in the afternoon of June 15. This was the day after he had sailed up the east coast of Howe Sound and survived “heavy squalls and torrents of rain” while camping for the night near Squamish.

Here is how he described the islands he observed in southern Howe Sound (Gambier, Keats, the Pasley group, and Bowen) while sailing along the western shore of the sound towards Gibsons: “The shores of these, like the adjacent coast, are composed principally of rocks rising perpendicularly from an unfathomable sea; they are tolerably well covered with trees, chiefly of the pine tribe, though few are of luxuriant growth.”

The exact spot where Vancouver and crew spent their first night on the Sunshine Coast is not known with certainty. In the B.C. centennial year of 1971 a memorial cairn was erected in Chaster Park (near Harry Road and Ocean Beach Esplanade) and a plaque affixed which reads, “Near this spot in June 1792 Captain George Vancouver, R.N. camped and gave Gower Point its name.” However, Vancouver’s account of the event suggests the more likely campsite was Gibsons Harbour.

There is confusion because Vancouver says he landed for the night around 9 p.m. near Point Gower, but the Point Gower identified on his chart appears to be the rocky headland we now call The Bluff, not the Gower Point we see marked on modern maps, which is near Chaster Park. When the new waterfront park (Winegarden Park) was being planned for the Gibsons Harbour area in 1993, historian and author Jim McDowell, then a Gibsons resident, was so convinced Vancouver had camped at the harbour that he petitioned the town council to either move the Chaster cairn there or erect a new cairn. Neither suggestion was implemented.

On June 16, Vancouver sailed the length of the coast between Gibsons and Pender Harbour. Here’s what he had to say about the land between Gibsons and Halfmoon Bay:

“This part of the coast is of a moderate height for some distance inland, and it frequently jets out into low sandy projecting points. The country in general produces forest trees in great abundance, of some variety and magnitude; the pine is the most common, and the woods are little encumbered with bushes or trees of inferior growth.”

After going through Welcome Pass, Vancouver noted, “the coast … is composed of a rugged rocky shore, with many detached rocks lying at a little distance.” That evening he made it as far as Francis Peninsula at Pender Harbour where he “found shelter in a very dreary uncomfortable cove,” probably Francis Bay, located within what is now Francis Point Provincial Park and Ecological Reserve.

The next day, June 17, he headed up Agamemnon Channel and into Jervis Inlet (somehow missing Sechelt Inlet or perhaps ignoring it) before setting up camp at Vancouver Bay (named by Capt. George Richards during his 1860 coastal survey). Vancouver observed:

“The shores we passed this day are of a moderate height within a few miles of this station, and are principally composed of craggy rocks, in the chasms of which a soil of decayed vegetables has been formed by the hand of time; from which pine trees of an inferior dwarf growth are produced, with a considerable quantity of bushes and underwood.”

For the next four days, Vancouver explored Jervis Inlet to the end of Queens Reach (he didn’t enter Princess Louisa Inlet because of the challenging Malibu Rapids, so he missed today’s biggest tourist attraction in the area), and then started the long trip back to Discovery and Chatham.

Encounters with indigenous inhabitants were infrequent in the area now known as the Sunshine Coast, though Vancouver had earlier communicated with many more in Burrard Inlet and northern Howe Sound. In his journal, Vancouver mentions friendly trade with perhaps two dozen: “From the civil natives who differed not in any respect from those we had before occasionally seen, we procured a few most excellent fish, for which they were compensated principally in iron, being the commodity they most esteemed and sought after.”

Vancouver’s book of his expedition, published in 1798, does not say where he stayed on the night of June 21, but it is likely he was back near the Sunshine Coast, probably on Worlcombe Island, one of the islands in the Pasley group, or Bowen Island. (Peter Puget’s journal says “that Night we reached the Cluster of Islands in Mid Channel off Noon Breakfast Point [Point Grey], where we stopped.”)

Early the next morning (Vancouver’s 35th birthday) he reached Point Grey where he had his famous – and highly unexpected – encounter with the Spanish explorers Galiano and Valdés who had arrived in the same waters only three days behind Vancouver. By the morning of June 23, Vancouver was back in Birch Bay, and the following day Discovery and Chatham were on the move again, heading towards a new anchorage further north in Desolation Sound to continue the survey, accompanied by the two Spanish vessels.

Vancouver’s exhaustive survey of the entire northwest coast was ultimately completed in 1794 and his two ships returned safely to England in September 1795. However, by this time Vancouver was in ill health and he died less than three years later, at age 40, on May 12, 1798. His book describing the adventure, A Voyage of Discovery to the North Pacific Ocean, and Round the World, was published posthumously later the same year.