Near the Bailey Bridge, about 10 minutes up the road from Mount Currie, archeologists and Lil'wat Nation community members are reshaping what collaborative research can look like.

For nearly two decades, Douglas College anthropology instructor Bill Angelbeck has worked alongside the Nation to investigate ancient village sites, often focusing on winter homes known as s7ístken (pronounced “ishkin”)—underground dwellings or "pit houses" traditionally used during winter.

Angelbeck and a team of students and volunteer archeologists have just completed a three-week dig as part of a multi-year project that’s working to use archeology and oral history in tandem to create a unified narrative for the Nation.

“We called it ‘interweaving narratives,’” Angelbeck explained to Pique.

“I see science as producing narratives just with scientific language. Just like oral tradition, [science is] subject to interpretation, and subject to refined understandings over time. We have scientific narratives about the history, and we also have oral history. How do we interweave those together?”

Lil’wat Land and Title Department coordinator Xzúmalus Roxanne Joe is excited about the proposition.

“We say that we’ve been here since time immemorial, and now this is giving science to point to specific dates,” Xzúmalus told a group of visitors to this year's dig site.

The project, a partnership between Douglas College’s anthropology department and Lil’wat Title and Rights, has grown from modest beginnings. Angelbeck has worked with the Nation since 2006, when he met Lil’wat archeologist and cultural technician Johnny Jones.

The work on their current project, Interweaving narratives: integrating oral histories with archeological investigations in Lil’wat territory, began in earnest in 2015, funded by an internal grant and focused on documentation of sites identified by Lil’wat knowledge holders. The team has carried out 10 archeological investigations on the territory, dating sites as ancient as 5,500 years old.

New technology at work

The current phase of the research is supported by a three-year, $360,000 federal grant that allows Angelbeck and the Nation to pursue more extensive investigations using cutting-edge technology. The team has employed both LiDAR—Light Detection and Ranging—and ground-penetrating radar (GPR) to uncover buried features across the landscape.

LiDAR uses laser pulses emitted from drones to strip away the forest canopy and reveal subtle depressions and elevations. The technology has been used worldwide to map sites obscured by dense vegetation, including Mayan temples and settlements in Central America.

“LiDAR sends millions of laser points per second,” explained Douglas geography lab technician Sasha Djakovic, who pilots a $40,000 LiDAR drone for the research time.

“When we strip the trees away in the post-processing, we’re left with a digital elevation model. Even changes in elevation of 20 centimetres will show up and point us towards village sites.”

Using the LiDAR technology has allowed the team to generate detailed 3D surface maps of excavation sites and create a database of old village sites in Ucwalmícwts, the Nation’s traditional language.

After a LiDAR drone has mapped the terrain from the air, GPR allows archeologists to peer beneath the ground’s surface. Using a device resembling a lawnmower, the team pushes the GPR unit over depressions that might indicate housepits to detect anomalies—subsurface features that stand out from the surrounding soil, like rock clusters, charcoal deposits and remnants of wooden beams.

The Bailey Bridge West site has been a focal point. The team uncovered 13 s7ístken at the site, including a 15-by-15-metre housepit—the largest yet identified in Lil’wat territory. They've dated some s7ístken at 1,700 years old and others at 2,700.

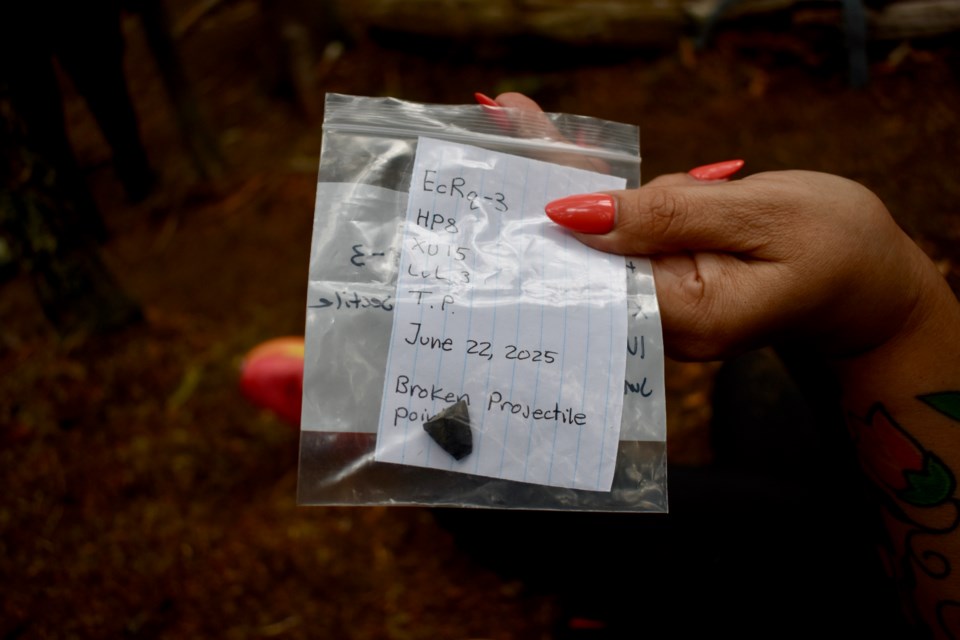

Each s7ístken contains different artifacts; from arrowheads with the Lil’wat Nation’s signature tang—an extra hook towards the bottom of the arrow—to beads and hearths and even the remnants of the pit-house roofs.

“That’s huge,” Angelbeck said of the findings. “Sometimes we put [excavation] units in and miss everything. It’s dispiriting for people who’ve volunteered a week of their time. But this time, every unit hit something.”

Challenging archeological norms

Xzúmalus has worked on the project since 2021. She emphasized its growing inclusivity. This year, with the dig running longer thanks to unprecedented grant funding, local students were able to visit the site and ask questions of Angelbeck’s team—with many expressing interest in pursuing archeology themselves.

For the last decade, Angelbeck’s team has included young Lil’wat Nation member Talon Pascal. Pascal first started volunteering on the site when he was 12, after Johnny Jones told his mom about Angelbeck’s dig.

He’s since grown into one of the crew’s most experienced members.

“He was always finding the arrowheads,” Angelbeck recalled. “He’s a flintknapper now and has made his own pit house and canoe.”

Pascal’s personal journey embodies the community-led approach the project is taking. His detailed knowledge of the territory, the lithic traditions and his connection to the land have made him a key contributor, said Angelbeck.

The project’s deeper aim is to challenge conventional archeological practices that have historically extracted Indigenous knowledge and artifacts without consent or benefit to Indigenous communities.

Historically, some archeological digs or anthropological ethnographies conducted on Indigenous territory treat findings as the intellectual property of the researchers, rather than belonging to the host Nation. Angelbeck cited particularly egregious examples of researchers demanding compensation for First Nations seeking transcripts from elder interviews.

The Douglas team is working to counter those practices.

“All the data we collect is Lil’wat’s first,” Djakovic emphasized during a presentation. “We use it for research, but only under their guidance. Finding sites is tricky—we don’t always know where they are—but we’re working to connect the known villages, and we’re doing that on [Lil’wat’s] terms.”

Next steps

The partnership’s success has rippled outward.

New sites identified through LiDAR are now officially registered with the provincial archeology branch, granting them protection from logging and resource extraction. Xzúmalus also noted the archeological record—combined with Lil’wat oral histories—is increasingly powerful in land claim efforts.

The Nation is not simply a stakeholder in the project—they're co-leaders. Their oral histories help guide where the digs take place. Their knowledge informs the excavation strategy. And their priorities shape the project’s next steps.

Lhpatq Maxine Bruce, who participated in a site visit, stressed the urgency of continuing the work while the community’s elders are still able to share their knowledge.

“I hear a lot of denialism about Indigenous people,” Lhpatq said. “It’s exciting you’ve taken on this kind of project, but the selfish part of me says: move faster. We don’t have very many elders left.”

The next phase of the project will focus heavily on oral history interviews. Angelbeck’s team has secured the necessary permits from the Lil’wat Nation and the provincial archeology branch to investigate additional sites identified through LiDAR. But the priority is to preserve the stories.

“One of the elders working with us has his own notebook of recorded stories,” Angelbeck said. “He’s very protective of it. Some stories can be shared, and some can’t.”

The careful stewardship of these histories stands in sharp contrast to the extractive or performative models archeology has often followed in the past.

“Sometimes archeological assessments are just a checkbox in a development process,” Angelbeck said. “But here, the goal is not to enable a project to go forward—it’s to enrich Lil’wat’s own story, to protect what’s there and to ensure the work is done in a way that centres Lil’wat priorities.”