Canada biggest cities have lost their green spaces at staggering rates over the past two decades, new data from Statistics Canada suggests.

On Thursday, the national statistics agency released urban greenness data for 1,016 towns and cities across the country. The results show that over the past 22 years, urban greenness dropped in every province—average falling eight percentage points across the country.

“A lot of people are putting a lot of effort into managing trees canopies and appreciating more vegetation in the city,” said Joanna Eyquem, managing director of Climate Resilient Infrastructure at the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation.

“The fact that the trend is still in decline is definitely worrying.”

On a hot day, dark-coloured surfaces like roads and rooftops absorb and trap heat, releasing it back into the air and creating “urban heat islands” of elevated temperatures. A well-placed tree, however, can save lives.

In neighbourhoods with dense tree cover, pedestrians can seek refuge under the shade of a tree. Perhaps more important is the cooling effect of water passing through a tree’s limbs and leaves. When that water evaporates into the air, trees and other plants can drive temperatures down across an entire neighbourhood.

Lose those trees and green spaces, and a city looses an important buffer against extreme heat and cold.

In its latest analysis of Canadian cities, the country's national statistics agency found decreases in green space were most pronounced in large urban population centres — those with more than 100,000 residents — where 10.5 per cent of urban greenness disappeared over the last two decades.

Calgary lost 16.5 per cent of its green spaces, the most of any Canadian city. Vancouver was not far behind, having lost 14.2 per cent of its average greenness.

Montreal, which had trailed Vancouver as Canada’s greenest big city 20 years ago, has since bumped Vancouver from its top spot.

On average, the bigger the urban area, the less area was classed as green. In large urban areas, greenness averaged 65 per cent, while 73 per cent of medium-sized cities and 86 per cent of small population centres were deemed green.

Which provinces had the greenest cities? Atlantic Canada out-ranked the rest of the country, with New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and Newfoundland and Labrador all averaging urban greenness above 90 per cent in 2022.

British Columbia fell almost 10 percentage points shy of Quebec and outranked Ontario by a slim 0.4 per cent.

In 2022, the greenest large urban population centres in Canada were:

- Saint-Jérôme, Que. (93.2%);

- St. John's, N.L. (92%);

- Kanata, Ont. (91.6%);

- Moncton, N.B. (91.5%);

- and Sherbrooke, Que. (90.6%).

Bleeding green, cities face confluence of drought, wildfire and heat waves

Statistics Canada found Milton, Ont., saw the biggest decline in green space of any large city, with a 30.5 per cent drop. The Ontario city was followed by Winnipeg, where greenness droped by 24.6 per cent.

Kelowna, B.C., tied Calgary with a 16.5 per cent decline in urban greenness, while Windsor, Ont., rounded out the cities with the biggest declines in urban greenness with a 15.4 per cent drop.

The overall decline in urban greenness concerns people like Alex Boston, who as the executive director of Renewable Cities at Simon Fraser University, was on the panel that produced a BC Coroners' report into the deadly 2021 heat dome. As Canada’s fastest growing city, he says Kelowna has done a good job at growing green spaces as it denisifies its core. Some of the city's biggest problems, however, are around the peripheral parts of the city, where urban sprawl is crashing into grasslands and forests.

“It's going to create growing vulnerability to flooding, to fire and to extreme heat,” he said.

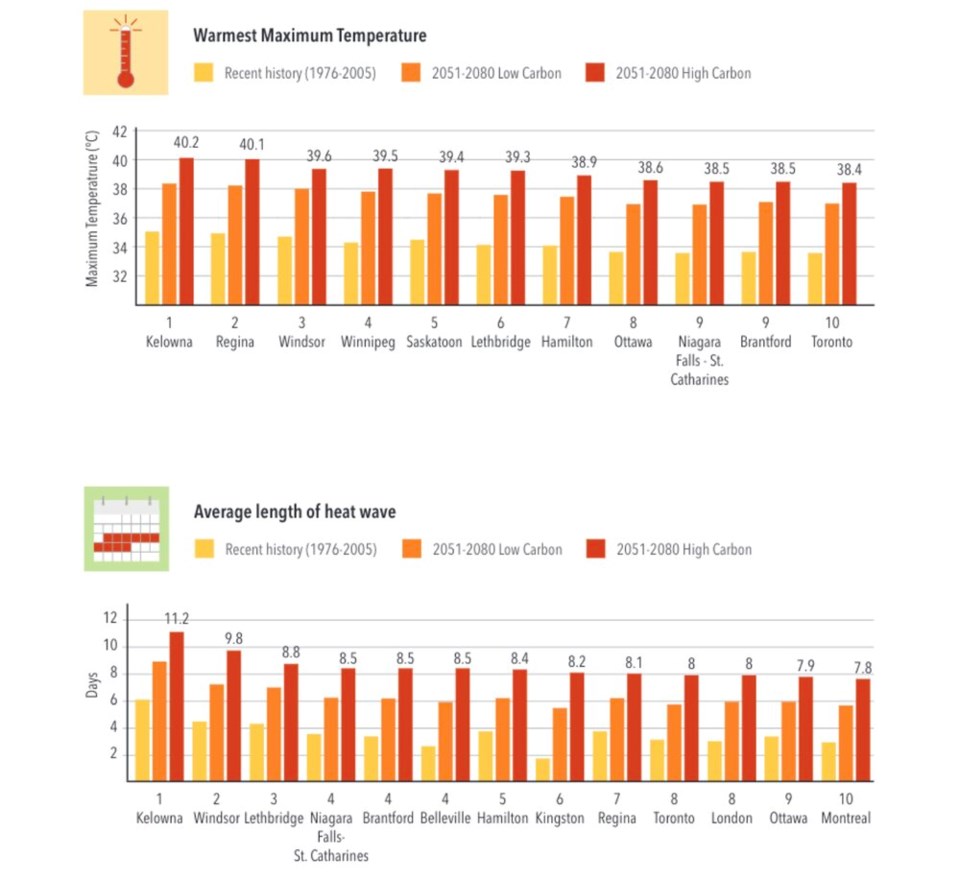

In a study released in April 2022, Eyquem revealed Kelowna is projected to face the longest-lasting heat waves and the hottest maximum temperatures of any major Canadian city.

Meanwhile, a confluence of wildfires and drought have threaten to transform forested areas into grasslands.

“We know that will be one of the epicentres of extreme heat mortality events. We know that will happen in Kelowna,” said Boston.

The situation appears equally critical in cities like Windsor and Winnipeg, which among Canadian cities, also face some of steepest declines in urban greenness and highest potential exposure to future heat waves.

“Reversing urban tree canopy loss and reversing the loss of vegetation is absolutely critical requirement for every local government,” added Boston.

From a parcel of land to a neighbourhood to the entire city or region, he says it’s time for the provincial government to pass laws that would set a bar for the minimum amount of green space.

“We actually need provincial governments to move into this space,” Boston said. “Because fundamentally, this is about reducing property and infrastructure damage... [and] reducing injury and loss of life.”

Mixed signals

Others warn the data needs to be interpreted with caution.

To measure “greenness,” Statistics Canada captured all green space on public and private property through satellite images and a tool known as the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI).

By filtering for specific wavelengths of light unique to plants, the index measures everything from grass all the way up to trees, and is often used to help understand vegetation density and changes in plant health.

“It’s basically showing you how much live vegetation there is,” said Amelia Needoba, senior urban forester at Diamond Head Consulting, a remote sensing firm in Vancouver.

But the index is also sensitive to soil moisture content. Because data was captured during the summer growing season, in a drought year, or when water restriction are in place, the NDVI greenness index would have captured a big drop as grasses and smaller vegetation die back.

Cities built in grassland ecosystems — think Kelowna, Calgary and Winnipeg — are most likely to natural swings between drought and wet years. Take a satellite photo at the wrong time, and you might capture a wildly different level of greenness.

In cities like Vancouver, greenness could be skewed by climate change: the drier the summer, the most soils will dry out across the city.

“There's a mix of signals in the data. It’s not just showing loss,” said Needoba. “I don’t think [Statistics Canada] has done a good job of explaining the variability.”

There's also a question over how the statictics agency decided to draw boundaries around cities. StatsCan also only considered census dissemination areas with populations of at least 1,000 people, living at densities of 400 people per square kilometre and above.

The results likely captured smaller vegetation in urban backyards and tree canopies in local parks. But in some cases, said Needoba, a regional park at the edge of a city may have fallen outside a densely packed census area and therefore was not counted as part of a city’s greenness.

Needoba said that despite a number of open questions, the Statistics Canada numbers aren't the only metric showing an erosion of natural urban spaces.

In much of Metro Vancouver, past studies have measured tree canopy cover — the share of a piece land covered by tree branches, stems and foliage when seen from above — by bouncing lasers from airplanes to the ground.

Known as Light Detection and Ranging, or LiDAR, the data shows an overwhelming declining trend in tree canopy cover across much of Metro Vancouver.

“There are declining trends in tree canopy cover in many population centres,” said Needoba. “Where we’ve got urban growth, I think that trend of decline is true.”

For fast growing cities built in grassland, like Kelowna, the loss of greenness is coming at the same time of year when drought, wildfire and the most extreme heat waves in Canada are most likely to encroach on a city.

If cities want to maintain their urban forests, Needoba says they will need to put more money and more thought into designing ways to capture water, provide shade and make buildings more energy efficient and able to stay cool.

Otherwise, she said, cities may lose their trees, and at the extreme end, transform into grasslands.

“All that information, It's sort of saying the same thing.”

.jpg;w=120;h=80;mode=crop)