B.C. researchers have developed a new tool to screen urine samples for hard-to-detect “designer drugs” poisoning the illicit drug market. The technology has found 31 new drugs so far and will allow laboratories to create clinical tests to rapidly identify new substances, and ultimately, save lives.

Conventional testing methods often miss hundreds of new psychoactive substances mixed with drugs like cocaine and heroin to maximize profits, often without the user's knowledge. That can lead to toxic and often fatal consequences, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal ACS Publications.

Because of the sheer number and speed that new drugs are being introduced into the market, labs have a hard time keeping up, and often don’t know what drug tests they should be prioritizing, said Michael Skinnider, the study’s lead author who carried out his work at the University of British Columbia.

“It's just not economically feasible nor is it practical for a lab, like the one at the BC Centre for Disease Control, to be setting up hundreds of new clinical tests every year,” said Skinnider, who is now an assistant professor at Princeton University.

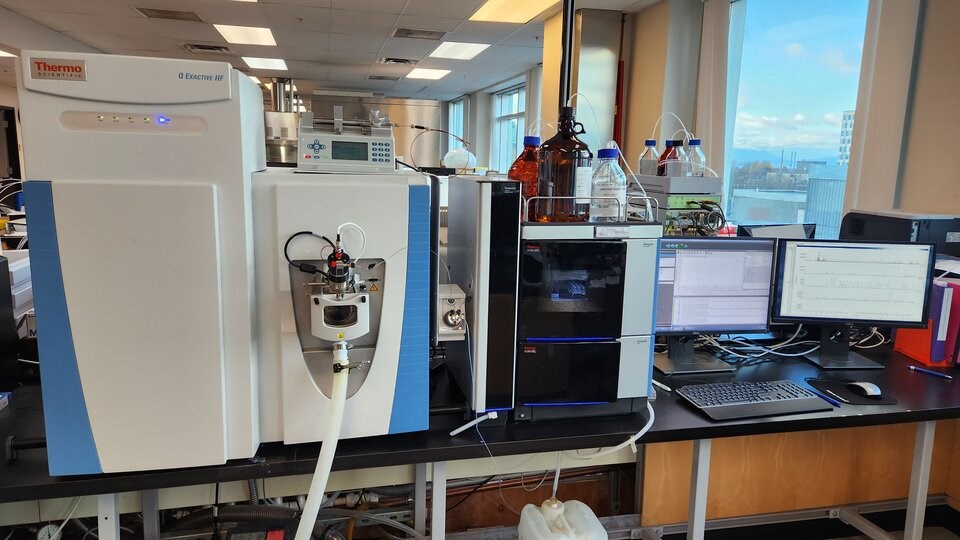

To get a handle on the vast and growing proliferation of toxic substances, the researchers analyzed 12,727 urine drug screens across B.C. using high-resolution mass spectrometry — a laboratory technique that shines a high-energy electron beam onto unknown substances to separate and identify what they are made of down to the molecular level.

The researchers then compared what they found with clinical lab data detected around the world showing the molecular anatomy of dozens of new and potentially dangerous drugs.

Over three years ending in August 2022, the researchers found more than 31 new drugs of concern across B.C., including benzodiazepines, stimulants and new synthetic opioids. One of those, fluorofentanyl, increased dramatically across B.C. in 2022.

“We really ought to be testing for this drug,” Skinnider said. “It’s got a tremendous potential to cause intoxications, overdoses and fatalities.”

If a patient sees a doctor under the influence of a new drug like fluorofentanyl, current tests will come back negative, leaving the physician in the dark with difficult choices on how to treat the patient. Public health officials and even law enforcement, meanwhile, will have little idea on where to start stemming the supply of toxic drugs if they don’t know what’s out there.

“You're sort of left wondering, what's going on here?” said Skinnider. “It’s really important to have this data to be able to tell there's some new drug that's sort of proliferating in the community in order to figure out what that response should look like.”

Testing for the presence of new substances requires researchers to produce a synthetic copy, known as a reference standard. Only then can researchers craft reliable and rapid laboratory tests to screen for the emergence of the dangerous new drugs in a wider population.

But those synthetic drugs cost money and creating tests out of them takes time. Skinnider’s new process identifies and narrows down what drug labs should prioritize for testing.

The tool — which was developed between researchers from the University of British Columbia, the BC Provincial Toxicology Centre, the chief medical examiner’s office in San Francisco and St. Paul’s Hospital in Vancouver — is currently being applied to clinical urine drug tests at the BC Centre for Disease Control.

“The idea is that this software will be run on a regular ongoing basis as part of standard lab operations,” Skinnider said. “They can kind of constantly be identifying drugs that are circulating, but which are not being detected by existing tests.”

The new lab protocol comes seven years after a rise in illicit drug overdoses prompted B.C. to declare a public health emergency. Between January and July of this year, 1,455 people died in the province from overdoses, the most in the first seven months of the year since the crisis started, according to the BC Coroners Service.

By September, just under six people were dying from drug overdoses every day.