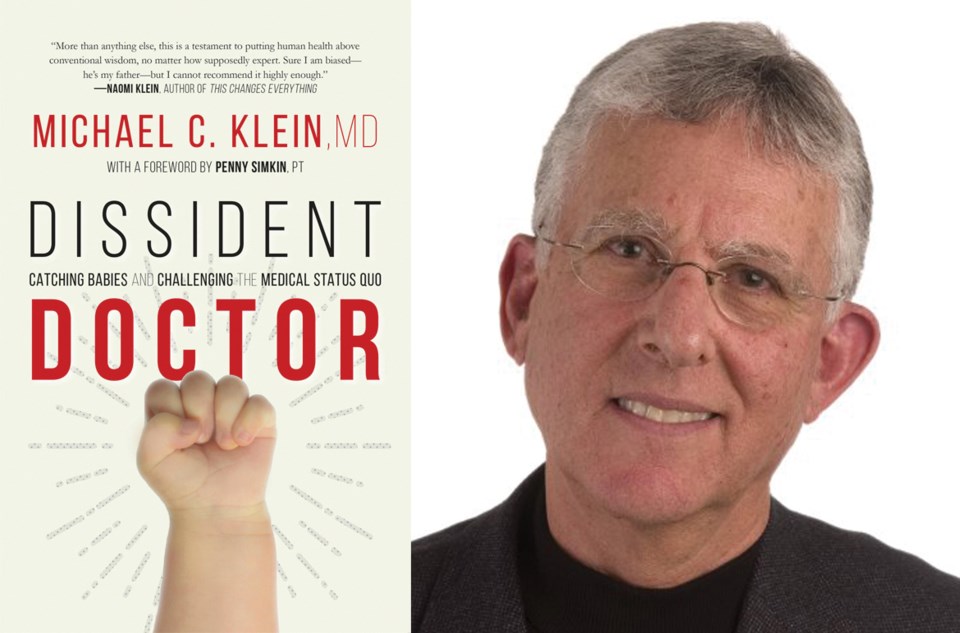

“I was a ‘red-diaper’ baby,” explains Dr. Michael Klein (Sunshine Coaster since 2003) in his highly entertaining memoir Dissident Doctor: Catching Babies and Challenging the Medical Status Quo (Douglas & McIntyre, 2018).

The term describes the child of activist/leftist parents – and his certainly were. Growing up in the U.S. during the 1950s McCarthy era, Klein developed both a passionate fervour for progressive politics and an equal determination to avoid any career that might force him to participate in authoritarian group-think. He chose medicine because he thought doctors were largely free from such political interference.

He was in for a rude surprise.

His first clash with medical group-think occurred not long after he enrolled in the Stanford School of Medicine to focus on pediatrics – the medical care of children, including childbirth. He discovered that modern medicine had been turning childbirth from a natural human event into a largely mechanical procedure. Birthing mothers were becoming, in effect, merely one of the hospital’s many devices used to produce a baby.

In Dissident Doctor, Klein gives us a vivid, blow-by-blow account of his impassioned crusade for a return to less high-tech birthing practices that focus more on the comfort and psychological well-being of the mother and her newborn. He lobbied for the return of the midwife and the doula. He promoted safe home births and separate birthing centres in hospitals. He railed against the excessive use of Caesarian sections, routine episiotomies, epidurals and forceps.

His second crusade – in many ways an extension of the first – was the creation and promotion of a team-based “family practice” approach, to counteract the tendency of today’s medical schools to train mostly specialists who then sit in their separate little silos and never talk to each other.

Real-life patients aren’t made of separate, disconnected parts, Klein points out -- and their afflictions aren’t either. For truly effective treatment, those specialists need to climb out of their silos and work collaboratively.

You don’t win wrestling matches with Big Medicine by charm and diplomacy alone, and Klein is quite capable of very direct, even abrasive assessments. That undoubtedly produced plenty of turmoil in his political life, but for this book, it’s a major advantage. His narrative voice is frank, amusing, mischievous and occasionally cranky by turns. The book is peppered with entertaining anecdotes, about everything from Klein’s years-long squabbles with the American army (think Alice’s Restaurant) to his experiences working with Ethiopian midwives in Addis Ababa in the 1960s.

There’s a heart-breaking account of his wife Bonnie’s massive stroke and astonishing recovery, and cheeky stories about his tangles with other doctors over their medical treatment of Klein’s patients and family members.

Klein left the U.S. for Canada in 1967 and subsequently occupied many lofty administrative positions here, including Head of Family Medicine at McGill University, and Head of the Department of Family Practice at BC Children’s and Women’s hospitals in Vancouver.

Mixing the lofty with the personal, this book brings it all together in a very engaging and readable way. He even keeps a lid on the medical jargon -- you don’t need a medical license to enjoy it.

– By Andreas Schroeder