I feel as though I have finally had that beer I wanted to have with John Horgan. Maybe two or three.

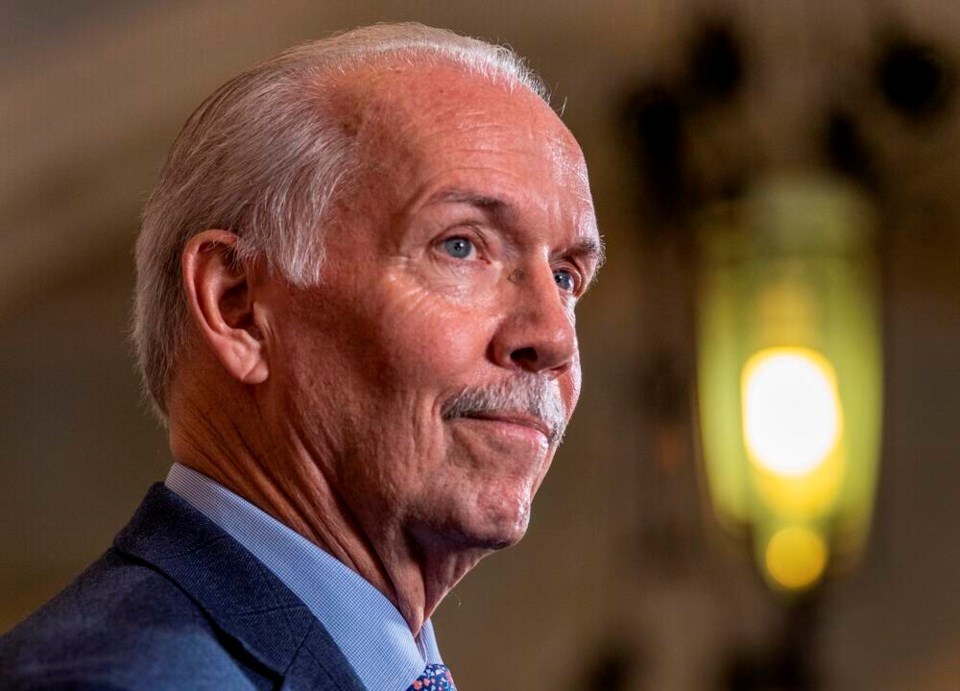

It has taken a posthumous book—one long series of tales, trials and tribulations, told in his inimitable voice—for me to at last unhitch any vestige of the performative politician from the very admirable human soul that left us last November.

Horgan told his life story after leaving the premiership and into battling cancer, even from a Berlin hospital bed in his final days, to journalist and longtime friend, Rod Mickleburgh, a former bureau chief of The Globe and Mail.

Only a handful of passages interrupt Horgan to set the context of a chapter; the book reads like one long evening into the night and the early morning listening to him. John Horgan: In His Own Words, will be released in mid-October by Harbour Publishing, and no amount of quoting or excerpting it does full-on justice to what you can hear as you read.

I have spent about 45 years now writing, broadcasting and managing newsrooms on politics in Ottawa, Toronto, Hamilton and Vancouver, and the late B.C. premier was the leader with the most intriguing path among all I watched. He was in no way born for the role, he made enough mistakes to rule out any run for office, he caught breaks more than made them, but by the time he left as the first two-term NDP premier, even former adversaries marvelled at the natural fit. In the interviews, Horgan noted the NDP banished—at least while he was there—"the narrative that the NDP can’t manage money.” He took special pride in showing that surpluses and social spending weren’t mutually exclusive. He reminded readers that eliminating MSP premiums, raising disability rates and funding schools were made possible by targeted taxes on those with higher incomes and the speculation levy on empty homes—and, of course, economic growth. He wanted to bury the old caricature of New Democrats as fiscally reckless—and he left office believing he had.

He left successor David Eby—he says remarkably little about him, which speaks volumes—a budget surplus since squandered.

There are some mea culpas, not all of them mild: the costly, ultimately cancelled plan to restore the Royal BC Museum, the onerous sick-leave provisions on small businesses during COVID, and a remarkable chapter on the failure to contend with the opioid crisis and how it shrouded any effort his government tried to make on dealing with mental health. That chapter struck me as having the most detailed reflection, regret and insight.

In his first term, Horgan created a ministry of mental health and addictions, under the health ministry, but he admitted it didn’t have the budget to have much impact. The monthly “body counts” of overdose victims distorted an important debate about how to set limits on harm reduction and the safe supply of drugs, and decriminalization led to open drug use and “a bit of a train wreck.”

Organized crime wasn’t curtailed, and the expectation in the pandemic that closing the borders might suffocate the supply of fentanyl was naïve—it simply generated a domestic industry. His belief in involuntary care for youth overdoses was opposed by the Greens he needed for support, not to mention some of his caucus, so it was shelved.

One mea culpa that broke NDP tradition, about which he had no remorse: the decisions to proceed on resource development, an awakening of the party in recognizing the need for a strong economy to pay for programs. He knew resource approvals unnerved many in his party, but he also knew credibility with business was critical. The province’s preeminent business leader, Jimmy Pattison, vouched for him in skeptical boardrooms, and it mattered more than a dozen speeches could.

“Those resource projects we approved boosted the economy, and the thousands of jobs helped a heck of a lot of workers and their communities. That was good for everyone,” he said.

COVID became the crucible of his premiership, but Horgan’s take is that the handling was proper—even if it exposed gaps in the system and relegated efforts on addiction and mental health. His least effective arguments are on the rationale for the 2020 snap election to gain a majority mandate; it remains hard to see how even in a minority government he would have lost power in the crisis.

There are many snippets of sound advice: “I’ve always felt that if you screw up, fess up. Everyone knows you’re not perfect. If you continue to deny the evidence before you because you don’t want to admit you’re wrong, people are not going to believe you, anyway, and they will think less of you.”

He suggests that, in opposition, the NDP “spent too much time protesting and not enough time building. If you want to yell at the building, great, but if you want to change things, you’ve got to get inside the building.”

What landed most with me were his constant refrains on relationships. Early in the book he recounts how a university friend became a lifelong one:

“I was the life of the party. I was the centre of attention. But what really stuck with him, and why we have remained friends to this day, is that I was always looking to see who was not included. How can we make the circle bigger so that everyone is part of the party? … I was always trying to keep as many people included as possible, always trying to make the table bigger.”

He later tells Mickleburgh: “For those stepping into political leadership today, relationships are critically important, and you can’t dispatch someone else to build those relationships. You have to do it yourself.” By that he means: “You don’t do that by direct mail, you don’t do that by standing on a stage. You do that by talking to people and listening to them and hearing what they have to say.”

Even his RCMP security detail became part of the story. As cancer weakened him, they literally carried him into his final treatments. “They didn’t have to do that,” he noted, “they’re just good people.”

For a man who insisted politics is built on relationships, for someone who quelled his temper by honouring his mother’s advice to not “burn his bridges,” it was a telling coda: the bridges you keep can matter more than the battles you win.

He was asked as he left office: “Would you want a formal state funeral?” He answered: “Do I have to be there?” But in his last discussions with his son, he left a simple request: “Just tell everyone I did my level best.”

Kirk LaPointe is a Lodestar Media columnist with an extensive background in journalism. He is vice-president in the office of the chair at Fulmer & Company.