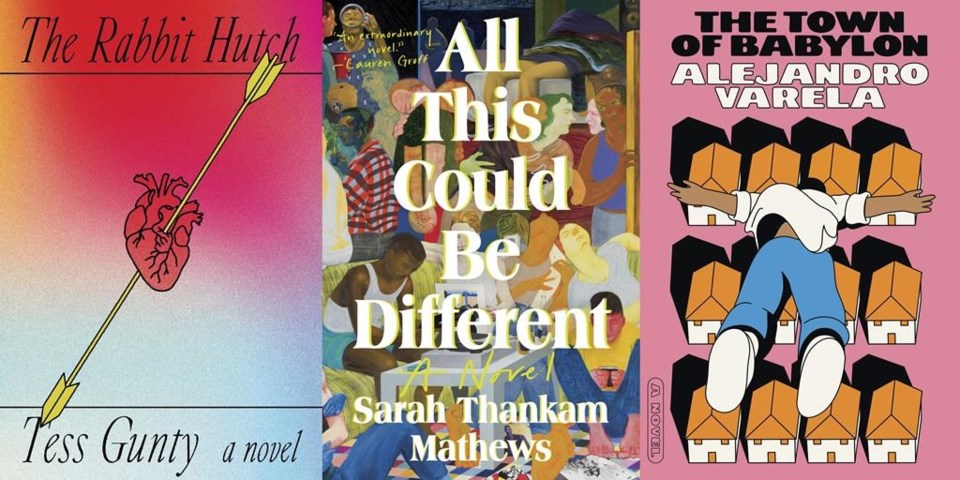

NEW YORK (AP) — In the minds and official records of the publishing community, Sarah Thankham Mathews is a first-time author. Her novel “All This Could Be Different” has been widely praised as a promising start for the 31-year-old Indian American, whose narrative about a young immigrant's personal and professional conflicts is a finalist for the National Book Awards.

But for Mathews and fellow nominees Tess Gunty and Alejandro Varela, the debuts that brought them recognition and acclaim are far from their initial efforts. Like countless other authors, the three finalists had written for years before the public was able to see their work, attempting novels and stories eventually set aside, discovering how best to structure their time, absorbing and discarding influences and styles as they searched for an elusive and precious literary grail: their own voice.

“So many of my early efforts were just me trying to find out what I wanted to write about,” Mathews says.

Fiction judges highlighted emerging writers for this year's National Book Awards ceremony, to be held Wednesday in New York. Gunty, Mathews and Varela were chosen for first-time publications and Jamil Jan Kochai for his second book, the story collection “The Haunting of Hajji Hotak." Gayl Jones is the category's lone established author, picked for her novel “The Birdcatcher,” published more than 45 years after her own celebrated debut, “Corregidora.”

Among the three newest authors, Varela had the most unorthodox path to his nominated work, “The Town of Babylon.” Varela, who turns 43 this week, did not major in creative writing but instead studied public health, receiving a master's degree from the University of Washington. His initial jobs included cancer research at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and teaching at Long Island University, but he also became interested in writing. In 2015, he published his first story, “Crime in the 21st Century," in the Southampton Review.

Over the next few years, he continued to write short fiction, learning along the way that he was better off “getting the words on the page without first trying to craft perfect sentences” and gaining faith in his ideas and talents. In “Town of Babylon,” he acted on a friend's advice and completed a full first draft without any initial editing.

“I was able to spread my wings and play a bit," he says of his novel, the story of a gay Latinx professor of public health who returns to his hometown for a high school reunion and relives his past in unanticipated ways. Varela said he was able to hone a “humorous, but self-conscious tone” he calls true to his personal experience.

“I'm a queer, Latinx son of working class immigrants," he said. "I didn't always feel I was welcomed into the conversations around me and when you don't feel you have a voice you become an observer and that leads to a kind of interiority. My writing allows me to have the kinds of conversations I have been having with myself.”

Gunty and Mathews each have been writing fiction since childhood. Gunty, born and raised in South Bend, Indiana, recalls an ambitious high school-era effort, an untitled novella about a dictator as seen from three women in his life. She had conceived it as the first installment of a trilogy but blames youthful indiscipline for never finishing the project, which was written on a desktop computer with no internet connection and is now lost forever.

As an undergraduate at the University of Notre Dame and a graduate student at New York University, she continued writing fiction, including a novella with the philosophical title “In Search of a Divine Hypotenuse.” But soon after leaving school, Gunty began a story that “wouldn't leave her alone,” often a sign of a book the author was meant to write.

She worked on “The Rabbit Hutch” for around five years, finding a new and deeper connection to her material — a polyphonic portrait of low-income housing residents in Indiana.

“In all my other attempts, I am not sure if I successfully accessed any voices different from my own; this book allowed me to inhabit each person a little more generously,” she says. Gunty, who recently turned 30, credits her own growing maturity and a more organized approach, including tacking up notecards inscribed with the book's major events around her room.

Mathews also was a teenager when she completed a novella, “Fire," what she calls a tragedy of star-crossed young lovers. She was dedicated to fiction writing and received a master's degree from the University of Iowa's Writers Workshop. But before discovering who she was as an author, she had to acknowledge whom she wasn't. Mathews was so influenced at one point by “The God of Small Things” novelist Arundhati Roy that she found herself writing what she called a “poor man's version” of Roy, a “very distinctive, musical style” that didn't become her.

“All This Could Be Different” was written quickly in 2020, and followed some seven years and hundreds of pages on a different novel she acknowledged suffered from “a certain unsteadiness” in its narrative. But out of her struggles, she forged a new voice, “an immigrant’s voice, where you see old ways of speaking fuse with the ways of the new country," and a new sense that the novel she was working on could “live out in the world."

“I wrote a manuscript with a beginning, middle and end in October 2020," she recalled. “I thought, ‘OK, I’m just going to read it,' and in the meantime I sent it to a few friends and other readers. What I felt when I got to the end of that first read was this sense of elevation and sort of a dream. What was written wasn't perfect, but it felt good and smart and alive.”

Hillel Italie, The Associated Press