For James Pawley, a retired University of Wisconsin professor living on the Sunshine Coast, the UN Climate Summit in Paris was even more important than another historic treaty negotiated in that city – the 1919 Treaty of Versailles that followed the end of the First World War.

Pawley explained why to a near-capacity crowd at Chatelech Secondary during an Elder U lecture on Jan. 12.

“I want you to realize that this is a big deal,” he said, going on to note that while the war’s most serious impacts were confined to Europe, “climate, on the other hand, determines what ecosystems can survive.”

He also told the crowd that, in his opinion, the agreement reached in Paris last December isn’t perfect and the promised greenhouse gas (GHG) emission reductions and other strategies are still “not enough to avoid really serious climate change.”

Pawley offered an overview of studies showing the impact of shifts in the climate, such as shrinking ice caps, the loss of boreal forest worldwide, glacial melt and longer, more frequent droughts.

He also said the research linking those impacts to human activity is the result of “the greatest deployment of scientific testing and analysis the world has ever seen.” When the floor was opened to questions, though, it didn’t take long for someone to try to challenge Pawley on the scientific evidence.

An audience member (who didn’t introduce himself, but claimed he was also a university professor with expertise in climate change) said, “I think everything that you’re saying is upside down, and I could give another lecture on climate that would be completely different from what you’re saying here.”

The speaker pointed to evidence for pre-modern periods of climate change that couldn’t have been driven by human activity.

Pawley didn’t have much chance to respond before the moderators intervened, saying while they welcomed questions, they didn’t want the event turning into a debate.

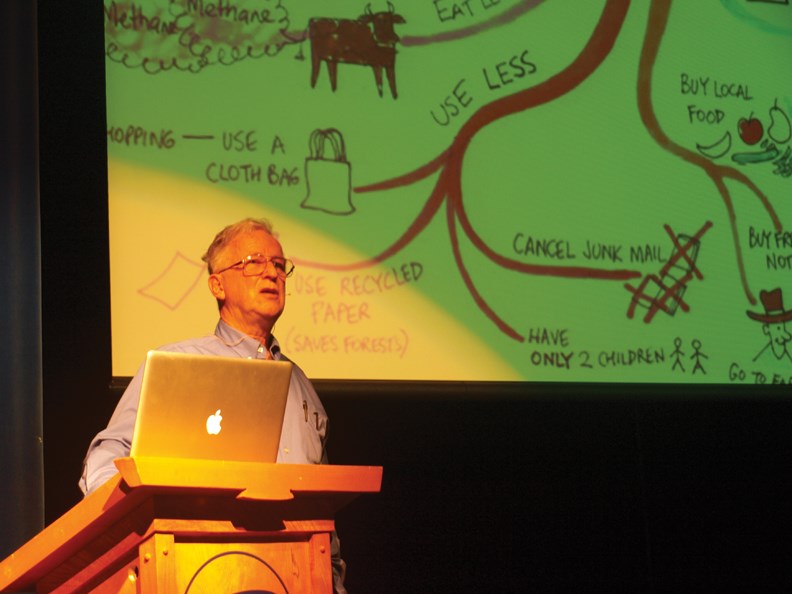

Pawley also used some of the time to highlight everyday changes people can make that would reduce energy use and emissions, like using a laundry line, taking public transit, building better insulated houses and heating with solar or geothermal.

In response to a question about whether it might be more important to focus on the bigger picture and push for government action, Pawley acknowledged those day-to-day things can be a bit of a distraction, “if we don’t do the other things, such as put a serious price on carbon, and act as though all this is all true and act as if we’re going to have to do something about it.”

That idea of putting “a serious price on carbon” developed as a main theme in Pawley’s presentation, which drew links between the economy, energy and climate impacts.

The economy, Pawley said, “is just a name for the system we use to decide how fossil fuel energy will be employed. Therefore, saving the climate requires a fundamental change in the way we get energy to run the economy.”

He said that change is already starting to happen, but there are two things that aren’t being done enough, or at all.

According to Pawley, there is a consensus among economists that carbon should be priced, at rates as high as $600/ton, and he praised B.C. for having one of the world’s first carbon taxes.

He told the audience pricing carbon has to go hand-in-hand with ending subsidies for the production and use of fossil fuels. He said the International Monetary Fund puts the value of those subsidies at about $5.4 trillion U.S. a year.

Pawley will be covering the same ground in a five-week Elder U course starting at Capilano University’s Sechelt campus on Jan. 19. For more information, see capilanou.ca