Howe Sound is the wrong place to allow tankers carrying liquefied natural gas (LNG), a leading opponent of the Woodfibre LNG project told Gibsons council in late June.

“Howe Sound is a narrow waterway. These ships are rather large. They are twice as big, twice as wide, twice as high as a BC ferry,” Bowyer Island resident Eoin Finn said. With tankers crossing several ferry lanes, he said, “the potential for spills and collisions is pretty serious.”

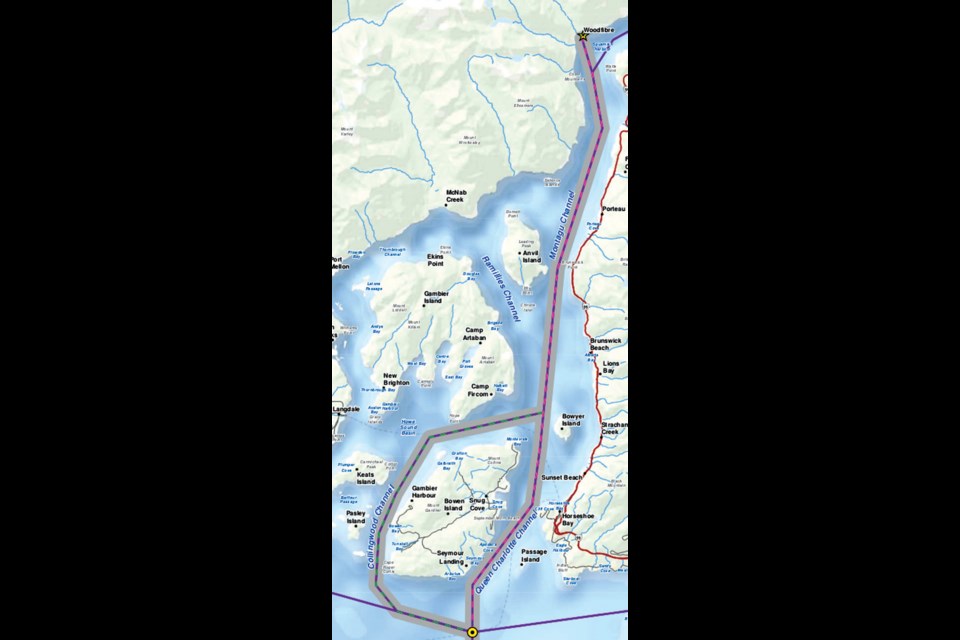

The Woodfibre LNG proposal would see about 40 LNG tankers per year transiting Howe Sound via Montague and Queen Charlotte channels. An alternate route would see tankers pass through Collingwood Channel, between Bowen and Keats islands.

“Even though it is a fairly small number, if there’s a rupture in the tank of one of these tankers, several nasty things can happen,” said Finn, a retired KPMG partner with a PhD in physical chemistry and an MBA in international business.

“These LNG tankers carry the thermal equivalent of 70 Hiroshima-sized atom bombs, so these are dangerous things. They’re classified as a class-A hazard. Other ships are supposed to keep away from them, seriously away from them.”

Finn said the international standard for safe distances from an LNG tanker is 1.6 km on either side of it, and “there are several places in Howe Sound where you don’t have 3.2 km between the shore and an island.”

Risk zones include Britannia Beach, where he noted there is a large proposed expansion of residential development; between the southern end of Anvil Island and the Sea-to-Sky Highway; between Bowyer Island and Hood Point (on Bowen Island); and between Horseshoe Bay and the southern end of Bowen.

“They are all at risk if there is an accidental or deliberate spill in the sound,” he said.

While the risk might seem minimal for the west side of the sound, he added, “if they do come on the other side of Keats, it might matter.”

A ruptured tank, he said, could lead to “a very big fireball” after the gas meets an ignition source, causing 50 per cent fatalities within 3.7 km.

“In that sense it’s very different from a bomb that explodes. But the difference to a person within 3.7 km of this event would be somewhat academic.”

Finn acknowledged the safety record of LNG tankers has been “pretty good” for the past 30 years.

“There have been collisions, there have been groundings, there have been leakages from the tanks, but no major fire and no major escape of LNG gas.”

One reason, he said, is that the tankers are owned and operated by oil and gas giants like Shell and ExxonMobil, who have a lot at stake, whereas the proponent of the Woodfibre LNG project “has never built or operated an LNG plant, ever.”

There are also very stringent rules in place for ports around the world, he said. Woodfibre, however, “is not an official port and does not have official port rules.”

Finn has been making the rounds to local governments across the region, asking them to urge Ottawa to ban the passage of LNG tankers in the Salish Sea.

He noted the Harper government strongly opposed the passage of LNG tanker traffic through Canadian waters in 2006, when there was a proposal for three LNG import terminals in Maine that would have seen tankers routed off the shore of New Brunswick.

The Woodfibre LNG project has been granted an export licence and is currently under review by the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office.