At Liz de Beer’s Klaywerk Studio and Gallery, a two-minute drive from the Langdale ferry terminal, kiln-fired pottery tells a story of cultural fusion. African antelopes and giraffes crown her ceramic vessels. Masks and figures embody the Madjadji rain queens, a matriarchal dynasty praised by Nelson Mandela for their cultural power. Fine-tipped porcupine quills perch like miniature sceptres in earthenware goblets.

“You can take me out of Africa, but you can’t take Africa out of me,” chuckles Liz. It was 26 years ago this summer that she and her husband Jan emigrated from South Africa. They touched down in Toronto, then moved to the West Coast during the historic snowstorm of 1996.

Bears and moose—icons of Liz’s adoptive Canadian homeland—prowl in formation around wide-mouthed bowls. Hand-painted silhouettes of evergreen forests adorn coarse-coated surfaces.

“What makes my style unique is the rawness of it,” says Liz. “And though I wouldn’t say Canada is raw, it’s huge. In Africa, where the animals live, even in places like Kruger National Park [a game reserve on the Mozambique border], it’s small and animals live behind a wire fence. Here, wild animals roam free. I want to incorporate the openness of Canada with the African style.”

The rough-hewn feel of her work links Liz to a formative memory. She was born on a remote farm where her father raised livestock. A river flowed through the pastureland.

As a child, Liz crouched on its banks and plunged her hands into the warm soil of the African subcontinent. “I always played with the mud,” she recalls. “I made little boxes and little houses. I always loved art.”

Her father urged her to become a kindergarten teacher. Three days before the start of university classes, a family friend told her parents, “Liz has made the biggest mistake ever. She should go to art school.”

They phoned a technical college on South Africa’s southeastern coast. A hasty meeting was arranged to review her portfolio. Eager to make a good impression, Liz dressed in stockings with neat shoes, her long ginger hair pulled into a bun.

“The first person we met was a young student in his third year and he looked like a real hippie,” says Liz. “He wore Moses sandals and had a long beard. My conservative dad turned to me and said, ‘I don’t know, my child.’”

In a cluttered office, the department head reviewed her sketches. Her mother sat on the room’s solitary chair, while Liz and her father squatted on boxes. Anxious minutes passed. Finally the official nodded: the earnest redhead could be admitted. Liz moved into the dormitory and began first-year general art studies.

Despite the last-minute adjustment in professional trajectory, Liz’s father was right about her talent for teaching. When she and her husband settled in Vancouver with their two children, she became a popular pottery instructor for teens and kids at studios across the North Shore.

Then a chance observation shaped the course of Liz’s life. “As I was giving classes at the Seymour Art Gallery, I noticed they were building a new community centre. I rented the art studio for pottery classes. Then I got to know the programmer and said, ‘Are you guys going to need a manager?’”

That question led to nearly a quarter-century as pottery studio manager at the Parkgate Community Centre. When she and Jan moved to the Sunshine Coast 17 years ago, she traveled each weekday to work at the studio near the slopes of Mount Seymour Provincial Park. She retired from the role this summer.

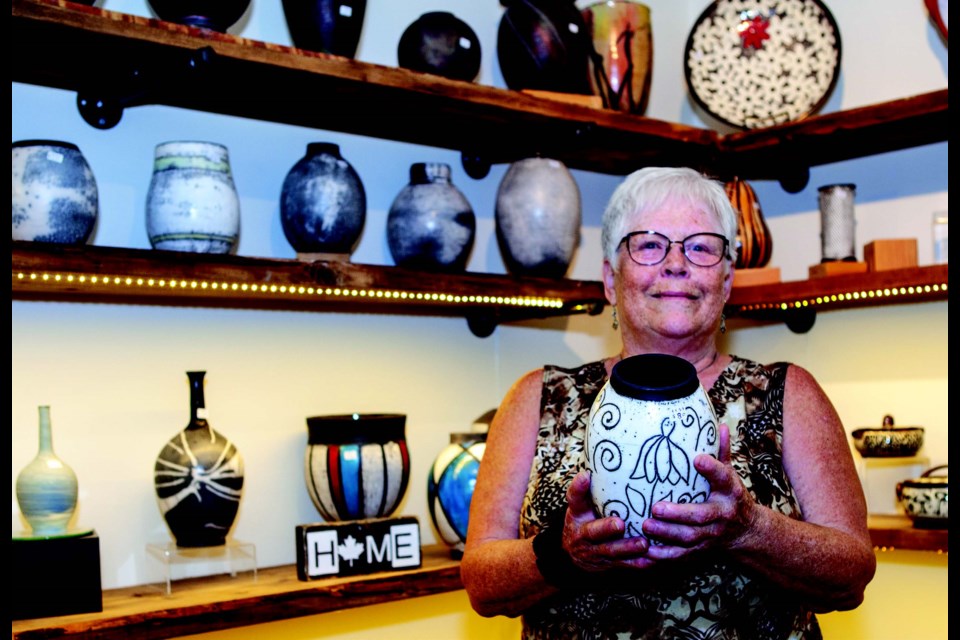

Meanwhile, Liz has become a fixture of the thriving Sunshine Coast ceramics community. Jan, a film industry veteran and himself an upcycle artist, suggested the name Klaywerk for Liz’s home-based studio. The ground-floor gallery and workspace is a popular destination on the annual Art Crawl and recently-launched Pottery Prowl.

“I’ve gone through a whole lot of different styles,” says Liz. “Most of my work is exhibition things that are just one of a kind.” A collection of thick scrapbooks catalogues her group and solo exhibitions. She harbours a special fondness for naked raku, a Japanese technique in which ceramics are removed from the kiln while still red-hot, polished but unglazed. Jan painstakingly records each of Liz’s original creations in a photographic database whose tally now exceeds 4,600 artworks.

Liz’s 2004 exhibition at the Silk Purse Arts Centre—The Spirit of a Rain Queen—crystallized her attachment to African Madjadji traditions. She used ceramics to fashion traditional apparel usually sewn from leather and beads, like the mapoto aprons worn by Ndebele women that depict the wearer’s biography through colourful designs. Ceramic drums and long-necked statuettes are still cached throughout her studio.

“Everything in this house speaks,” says Liz.

After her inaugural show on the Sunshine Coast, almost two decades ago, she and Jan buried one of her clay pots at a secret location near Port Mellon. The act symbolized the potter’s reciprocal relationship with the earth.

For an artist whose creative journey began with mud-streaked hands on the African veldt, it’s hard to imagine a better way to cement a place in the Sunshine Coast’s cultural landscape.

Browse to lizdebeer.com to learn more.