Part 1 of this article appeared in last week’s Coast Reporter, Sept. 14.

Travelling in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland this summer, I crossed borders and yet found more similarities than differences. True, the Canadian dollars, UK pounds, and Euros got muddled in my wallet, but otherwise the chief differences were the mailboxes: the Republic’s green and the North’s red. That and the Irish language and its distinctive Celtic script throughout the Republic. Nowhere were the similarities stronger for me than on the moors and mountains I marched across, and especially at the Seamus Heaney Home Place in Bellaghy, Northern Ireland, where I was strongly reminded of my long-ago English childhood on a farm.

My father died years ago, but this guided part of my holiday brought back the memory of his work and the farm where I grew up. The smell of sweat on his hair and on his work clothes. His gritted jaw when we hoisted sacks of wheat and potatoes and his muttered, “I’ll lift, you grunt.” The way he stared, thinking hard, at bullocks in their yard, at heifers on the hillside.

For years I had found little in poetry, until I began to read Seamus Heaney’s poems, which suddenly illuminated our common farm childhoods. My seven-day hiking tour included a morning in the Nobel Prize poet’s farming village of Bellaghy, 34 miles north-west of Belfast, which encouraged me to recall that damp and earthy air of my childhood. Out of such earth Heaney, son of a modest farmer in this little Irish village, went on to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1995, joining writers like Alice Munro, Samuel Beckett, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Toni Morrison.

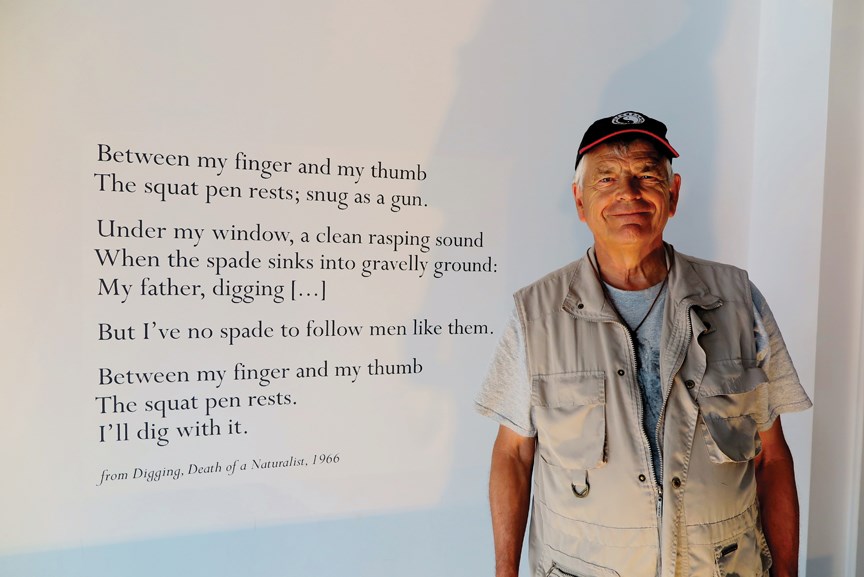

The Home Place – magically named – is a magnificent new arts centre with an expansive series of galleries, where I was not the only visitor to breathe deeply and hold back tears. We heard his gentle yet passionate voice reciting the poems while we followed his words on illuminated panels, beside backlit photos of Seamus and his family and neighbours at work. We examined his manuscript handwriting and the displays of related objects and landscapes. It’s no wonder that when I mentioned him elsewhere in Ireland, so many strangers, folks on the street and in pubs, ordinary Irish people, said in passing and without pretension, “Oh yes, Heaney, he’s our man.”

The Victorian writer Matthew Arnold cynically joked that in English-speaking countries the word poetry will clear a crowd quicker than a fire hose. So Arnold would have been amazed to see, as I saw later in Derry, a framed photo of Seamus Heaney tacked on the wall of a side-street café. On an ordinary café wall: a Nobel winning poet.

Heaney’s younger brother Hugh has remained a farmer in Bellaghy, while Seamus went on, with his smallholding parents’ blessing, to university, to Harvard, to worldwide recognition and publication. Hugh Heaney had watched the Home Place being built, and said that it had been given a perfect name because it had always seemed, in Seamus’s writing, that he had never left the place. Yet his vital short poem “Digging” is now embedded in school reading lists across the world. Seamus’s honouring of and respect for the manure pile, anvil, spade, cattle yard, and coal truck brings us all back from airy philosophy to the life here at our feet, lit anew by Heaney.

Later our tour paused in the ancient city of Derry, which U.S. President Bill Clinton visited in 1995 as part of the Northern Ireland Peace Process. Clinton, being a literate man, and Heaney were already acquainted, and Clinton chose some of Heaney’s lines to quote in an official speech he made there.

Exhilarated by daily hikes and intervening scenic drives in the guide’s minibus, I later dived into the rich bustle of Dublin, the Republic’s capital. There, in the centre, at the impressive Bank of Ireland building, we found an entire floor given over to Heaney’s and Ireland’s history, curated by the National Library of Ireland. In there I saw some of the many thoughtful postcards that the busy yet considerate Heaney had taken time to scribble to one and all enquirers; studied his fascinating handwritten changes to his manuscripts and to printers’ proofs; and watched recorded interviews with other artists reflecting on his writing. And again, outside in Dublin and here among the building’s custodial staff, I noticed how firmly and fondly Irish people held Seamus Heaney to their hearts.